Introduction

by Linda Dittmar and Pamela Annas

In drafting our original Call for Papers, we did not think of this cluster in terms of “Public Pedagogy.” We simply wanted to assemble essays about a range of radical teaching practices that take place outside the traditional classroom and the giant MOOCs that are replacing it. Such discussions have appeared in Radical Teacher in the past, though they were rare and appeared piecemeal. (Exceptions are RT’s art activism (#89), prison (#88), and food (#98) clusters.) What drew us to this teaching was our sense that interesting work is in fact occurring informally, outside the “business as usual” of most education, and that it would be useful to think of this work across contexts and subject matter.

In drafting our original Call for Papers, we did not think of this cluster in terms of “Public Pedagogy.” We simply wanted to assemble essays about a range of radical teaching practices that take place outside the traditional classroom and the giant MOOCs that are replacing it. Such discussions have appeared in Radical Teacher in the past, though they were rare and appeared piecemeal. (Exceptions are RT’s art activism (#89), prison (#88), and food (#98) clusters.) What drew us to this teaching was our sense that interesting work is in fact occurring informally, outside the “business as usual” of most education, and that it would be useful to think of this work across contexts and subject matter.

The result is suggestive, though hardly comprehensive or exhaustive. Certain interesting proposals—about teaching mathematics, dance, and creative writing workshops in union halls—never came to fruition. Others never surfaced, notably a range of work underway with veterans or articles about climate and the environment. Teaching in refugee camps, radical home schooling, teaching in protest sites and movements such as Occupy and the Dakota Pipeline protest, alternative health education, and improv political comedy workshops were also on our mind but did not arrive in the mail.

The articles we do present in this issue provide a provocative beginning for thinking about public pedagogies. Their discussions—Margaret Gulette on a community based high school in Nicaragua; Nan Bauer-Maglin on creative writing mentoring in NYC; Travis Boyce on crowd learning on sports and race through social media; Jyl Lynn Felman on feminist pedagogy for seniors; Stevie Ruiz and students on a collaborative mind mapping project in environmental justice; and Donna Nevel on community teaching about Israel/Palestine and the Nakba—point to fresh ways of thinking about renegade pedagogies. Two poems by Jill McDonough provide vivid connections to teaching in prisons and in summer camps for adolescents. The focus throughout this issue on extra-institutional spaces and discourses implies a critique of the market logic of neo-liberal education and a concern with social justice that is to varying degrees activist and radical in its intent.

Rooted in critical pedagogy, cultural studies, and feminist and anti-racist practices, it is a teaching and learning “against the grain” that critiques and resists the reproduction of inequalities in light of the ongoing privatization and de-politicization of mainstream education. It is a communal, coalition-building pedagogy that serves excluded populations by positing a resistant, decentered, and disruptive engagement with knowledge and culture. Ranging between ameliorative and transgressive, this pedagogy seeks to disrupt and transform the dominant configuration of knowledge and understanding by positing dissent as a context for a critical, empowering education. Challenging the strictures of power, it interrupts the normative enforcement of injustice and creates opportunities for alternative perspectives and voices to engage in social transformation.

It should be noted that attractive and even utopian though it may sound, the concept of public pedagogy is vague and open to many applications, both regarding what “public” means and what “pedagogy” is appropriate for it. Gert Biesta (2012), building on Hannah Arendt’s definition of freedom as action, argues that rather than seeing public pedagogy as a pedagogy for the public or of the public, public education should “work at the intersection of education and politics… [T]he public pedagogue is neither an instructor nor a facilitator but rather someone who interrupts.” Biesta1 offers as illustration the staging of artistic interventions in public spaces. Sandlin, O’Malley and Burdick (2011) conclude their carefully researched review of the field by noting that the usefulness of the term public pedagogy has been compromised by the mythologizing and totalizing claims attached to it.2 They stress the need for careful and nuanced research in order to refine our understanding of that concept, listing many “shoulds” that researchers need to undertake.

Among others, Sandlin et al.’s “shoulds” include the need for careful study of the relation between theory and practice (“empiricism”) regarding how educational sites assigned to this rubric of “public education” actually work. Another nagging question their review lets drop concerns the extent to which education is communally constructed or top-down. Is it education for the people, by the people, or with the people? Extending this question to the present RT cluster of articles we also note the looseness of the term radical in this context, encompassing the differing goals of education for individual empowerment and education to enable collective action for social change.

Most immediately, these articles invite us to think about our own teaching, inside as well as outside of conventional institutions, with an eye for the renegade possibilities that can in fact occur in any place where teaching and learning aim to embody transformative praxes.

The essays collected here were not written with the term public pedagogy in mind, let alone any top-heavy theoretical thinking that aims to distill a field of pedagogy from the assumptions and practices that happen to have joined under this umbrella. Rather, they point us “toward” thinking about public pedagogy and about a teaching that exposes the power and politics at work within culture. Is this activism in itself? Will it lead to activism? Most immediately, these articles invite us to think about our own teaching, inside as well as outside of conventional institutions, with an eye for the renegade possibilities that can in fact occur in any place where teaching and learning aim to embody transformative praxes.

CLICK HERE TO READ THE FULL ISSUE!

Notes

1. Gert Biesta, “Becoming Public: Public Pedagogy, Citizenship, and the Public Sphere,” Social and Cultural Geography, 13:7, 683-697.

2. Jennifer A. Sandlin, Michael P. O’Malley, Jake Burdick, “Mapping the Complexity of Public Pedagogy Scholarship: 1894-2010.” Review of Educational Research, September 2011, Vol.81, No.3, 338-375.

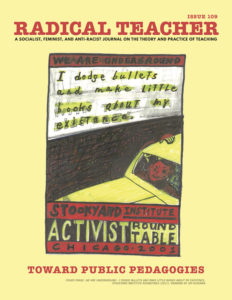

Cover Image: