Introduction: Carrying the Banner of Socialism

by Michael Bennett

A space on the agenda at the end of every Radical Teacher board meeting is reserved for a political discussion—sometimes based on an article or articles that a board member has circulated in advance, other times focusing on a topic we hope to address in future issues; occasionally the discussion arises from email exchanges about recent political developments; and not infrequently it’s a topic that someone throws out on the spur of the moment. If the meeting has gone on too long, we have been known to dispense with the political discussion altogether (out of exhaustion, time constraints, or, lately, depression at the political moment we inhabit). It’s difficult not to get discouraged politically in the wake of the most recent presidential election, but this fact also generated my favorite recent topic, which carried over two board meetings: What does one do to remain hopeful in these dire times?

My own answer to this question was to focus on the counterreaction to Trump, especially among those who are generally considered “college-aged.” I am encouraged by the fact that young people currently view socialism more favorably than capitalism (Magnus, Rampel), they supported the one self-described “democratic socialist” candidate in the most recent presidential election by a significant margin over any other candidate (Blake), and they comprise the largest bloc of members contributing to the growth of Democratic Socialists of America (DSA). DSA, which doubled in size during Bernie’s campaign, and doubled again after Trump’s election, has become the largest socialist organization in the United States since the turn of the 20th Century (Williams). For someone who has been a member of DSA since I was college-aged, this development has been both surprising and encouraging, reenergizing my commitment to the growth of the organization. After taking early retirement from Long Island University, I joined the national board of the DSA Fund (the educational branch of DSA). Many of my Radical Teacher colleagues have been enthusiastically supportive of this development, for which I am supremely grateful.

I should point out, however, that Radical Teacher is resolutely non-sectarian, and the views presented here are my own. We don’t end RT meetings by secretly transforming into a Maoist cell group. In fact, the RT board screens out sectarians who feel that there is only one true shining path to liberation. This non-sectarianism is what attracted me to both RT and DSA. For me, the D in DSA is crucial. I’m not entirely sure what a socialist future looks like, but I consider that a strength. I think that the future should be arrived at through pragmatic change that is democratically determined. It seems clear to me that this future would include healthcare for all, guaranteed food & housing, and fully financed free public education from nursery school to graduate school. But we will have to wait and see.

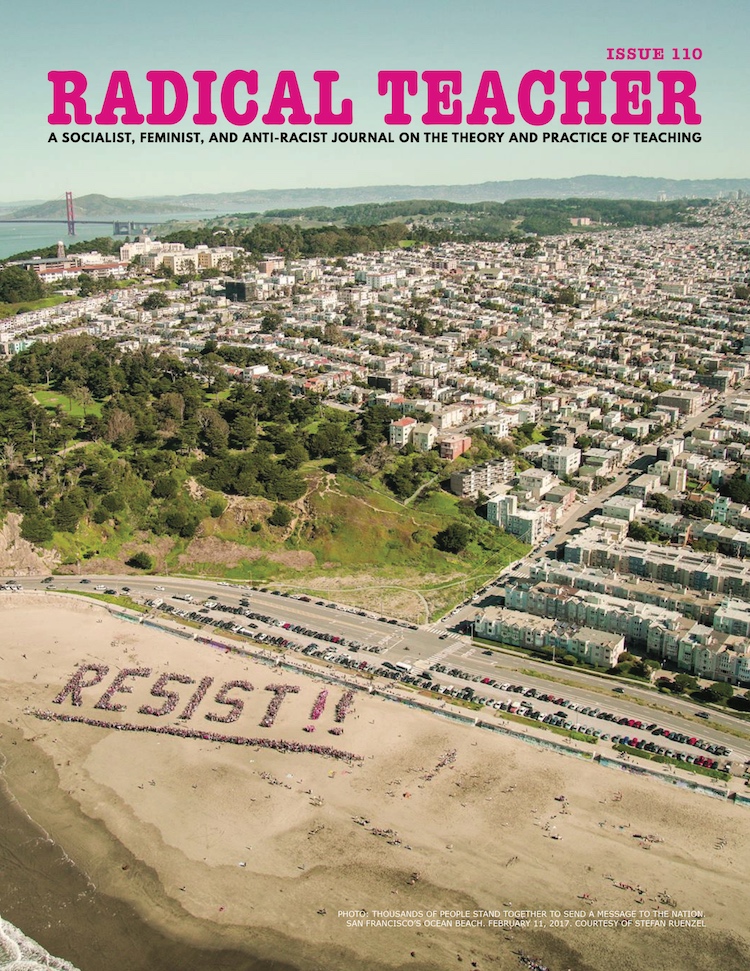

Though not tied to any one vision of a socialist future, Radical Teacher is committed to socialism. Not long ago, we revisited the subtitle of our journal—“a socialist, feminist, and anti-racist journal on the theory and practice of teaching”—and decided that we are still invested in the word “socialist” and not just “anti-capitalist” or some other word that completes the triumvirate of gender, race, and class. What’s more, we are dedicated to what has come to be called “intersectionality”: the ways in which class, race, gender, and other modes of social classification are imbricated with one another (Collins, Crenshaw). So, for us, the kind of feminism engaged in by radical teachers is simultaneously socialist and anti-racist; anti-racist thought needs to be grounded in gender and class analysis; and socialism is always inflected through race and gender. This proposition is at the core of radical teaching.

As you might imagine, adherence to these core beliefs means that we end up rejecting a large number of submissions that come our way. For queries and essays that are not submitted for a particular themed issue (those go to the editors of that issue), the manuscript co-editors, Sarah Chinn and I, are the first line of defense. We weed out essays that don’t have radical politics, fail to address the theory and practice of teaching, or are so poorly written that we can’t imagine the author(s) making a successful revision. All the essays that make it past this initial cut are sent to two readers who advise us on the next step: Reject, Resubmit for Review, Revisions Required, or Accept. The answer is almost never “accept as is.” Essays typically need to add more about the nuts and bolts of teaching (the “practice” part of theory and practice); explore how and why the teaching described is “radical”; and/or need work on grammar, phrasing, and structure. Unlike many journals, however, we are willing to work closely with authors on multiple revisions if we feel that a publishable essay might emerge from this process.

Among the most frustrating back-and-forths are those about what counts as “radical.” We get far too many essays that are liberal or well-intentioned, or that describe themselves as “critical” or “progressive,” but they’re not radical. They might, for instance, be feminist but they’re not socialist feminist. They might address race, but from the perspective of a touchy feely multicultural or tolerance model. They might be anti-capitalist, but with a doctrinaire Marxism uninflected by gender and race. They might embrace a radical politics, but in a highly technical language that runs counter to our commitment to provide a space for all educators, from pre-K to doctoral. Sometimes people are willing to be challenged about their politics, and the result can be a rather startling realization on the part of the author about the differences between liberalism and radicalism. Sometimes we have a parting of the ways because even multiple revisions aren’t able to craft an essay that fits into a journal called Radical Teacher.

We also receive a pleasingly large number of essays that meet all our criteria, sometimes after much revising but also on occasion with very little back-and-forth. In the case of the current issue, we were particularly fortunate to work with authors who for the most part fully responded to reviewers’ comments without further prompting by Sarah and me. These authors clearly articulated their radical politics, while keeping an eye on both pedagogical theory and practice. Many of the essays emphasized how challenging but necessary it is to engage in radical teaching within the constraints of this difficult political moment.

Dan Colson’s essay “Teaching Radically with Koch Money” and Jaime Madden’s “Instructor or Customer Service Representative?: Reflections on Teaching in a For-Profit College” directly confront two of the realities of teaching in a time of conservative and neoliberal assaults on higher education: having to rely on corporate money to fund colleges and universities (Colson) and trying to work within the constraints of the for-profit sector (Madden). Dan Colson narrates his experience of applying for a grant from his university’s Koch Center for Leadership and Ethics, and teaching the redesigned Survey of Later American Literature the grant funded. Colson explores the Koch Center’s rhetoric, focusing especially on the space between their putative neutrality and their clear embrace of right-wing definitions of freedom. The course Colson taught redeployed the Center’s language about “leadership,” “ethics,” and “freedom” in order to foreground their circumscribed notions of these concepts. Colson’s essay concludes with some thoughts about how to resist higher education’s seemingly inexorable shift rightward by reshaping the language and emphases of organizations like the Koch Center, ultimately suggesting we combat these neoliberal tendencies by battling them directly on the ground of “freedom.” Jaime Madden’s essay offers a critical retrospective engagement with her experience teaching at a for-profit institution of higher education. Madden interrogates the institution’s “customer service orientation,” which created distinctive expectations for how instructors interact with their students and for how they are expected to foster this orientation in student behavior. Madden provides an interesting tour of the institution’s spatial configuration and marketing campaign before focusing on two aspects of the for-profit educational experience: 1) the classroom experience within a generic sociology course that attempted to work against the customer service orientation; and 2) a close reading of a course textbook assigned to all incoming students, which reveals most clearly the dual operations of neoliberal individualism and a customer service orientation. Both of these essays explore the complex and calculated negotiations of teachers and students with academic capitalism.

Colson’s essay concludes with some thoughts about how to resist higher education’s seemingly inexorable shift rightward by reshaping the language and emphases of organizations like the Koch Center, ultimately suggesting we combat these neoliberal tendencies by battling them directly on the ground of “freedom.”

Though most submissions to Radical Teacher focus on post-secondary education, we are also happy to publish germane essays that come our way about non-traditional teaching environments (community centers, labor unions, archives, …) and primary or secondary schools. The latter is the topic of Rachel Jean’s “Promoting Social Action through Visual Literacy: New Pioneer & The Labor Defender in the Secondary Classroom.” Given the task of developing her students’ “visual literacy,” Jean chose to disrupt her students’ expectations based on contemporary visual media by presenting them with left-wing political magazines from the 1920s-1930s: Labor Defender and New Pioneer. Jean maintains that using these unfamiliar and politically charged materials helped her students to reach the learning goals of visual literacy while broadening their cultural values and encouraging their ideals of social action. Her essay is another example of how teachers can maneuver within constricting circumstances (in this case, core standards for visual literacy) to achieve radical ends.

The other two essays in this issue focus on historical and contemporary anti-racist social movements and their representations. Tehama Lopez Bunyasi’s “Structural Racism and the Will to Act” describes how today’s Black liberation movement inspired her to revise a graduate course on race and conflict, encouraging students to think about how contemporary institutions and social practices determine the value of life at the color line. Initially, Lopez Bunyasi was inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement to revise her curriculum to more directly address contemporary manifestations of the Black radical tradition; in the epilogue, she ponders another round of revisions given the outcome of the 2016 presidential election. Jennifer Ryan-Bryant’s essay “Anti-Racist Pedagogy In and Against Lynching Culture” develops a specifically anti-racist pedagogy to address the legacy of lynching and its representations in the United States. She and the students in her class were anxious to avoid replicating the ways in which the topic of lynching is often circumscribed (through the assumption that the term only applies to the past) or commodified (through marketing horrific images). Ryan-Bryant and her students worked to connect earlier anti-lynching campaigns by Ida B. Wells and others with contemporary movements to resist the harms inflicted on black bodies. They also made a conscious decision mostly to eschew visual images of lynching so as to avoid replicating the specularization of the black body evident in early postcards of lynchings that were circulated as souvenirs of white supremacy.

The fact that both of these essays focus on structural racism as an outgrowth and enforcer of predatory capitalism is a perspective shared by the author and subject of the interview reprinted from Truthout.org in this issue of Radical Teacher. Chris Steele’s “Decolonizing the Classroom: Embracing Radical Internationalism” investigates ways to decolonize the classroom through employing internationalist Black radical historical perspectives. The article features an interview with the prolific historian Gerald Horne, who discusses the importance of how history is framed in the classroom regarding people of color, colonialism, resistance, and representation. As we head from 2017 into 2018, the internet has blown up over the disagreement between prominent Black intellectuals Ta-Nehisi Coates and Cornel West. Though one can critique West for the tone and strategy of his critique of Coates, it’s difficult for radical teachers to disagree with many of his claims. For instance, West argues that Coates’s “gross misunderstanding of who Malcolm X was—the greatest prophetic voice against the American Empire—and who Barack Obama is—the first black head of the American Empire—speaks volumes about Coates’ neoliberal view of the world.” West maintains that it is necessary to confront such a neoliberal view because he stands “with those like Robin DG Kelley, Gerald Horne, Imani Perry and Barbara Ransby who represent the radical wing of the black freedom struggle. We refuse to disconnect white supremacy from the realities of class, empire, and other forms of domination—be it ecological, sexual, or others.” In republishing this interview with Gerald Horne, Radical Teacher is also declaring where we stand: at the intersection of socialist, feminist, and anti-racist movements contesting the center’s neoliberalism and the right wing’s combination of libertarianism, sexism, and white supremacy.

It is difficult not to get discouraged by the apparent ascendency of this right-wing version of the triumvirate of class, sex, and race. And many of my Radical Teacher colleagues have in fact been quite depressed by the forces unearthed in the wake of Trump’s victory, as have I. However, working with DSA and interacting with students, teachers, and others who proudly carry the banner of socialism into a new era has made me more sanguine. I truly believe that the most recent election is the last or next-to-last gasp of white supremacy as a determining factor in presidential elections (though it will linger, as it has since the founding, in the marrow of the body politic). The counterreaction to Trump gives me hope for the future. This hope is shared by the authors published in this issue of Radical Teacher. Since its founding, this journal has been dedicated to socialism, feminism, and anti-racism; we will continue to act on this dedication; thank you for joining us in this freedom struggle.

Works Cited

Blake, Aaron. “More Young People Voted for Bernie Sanders than Trump and Clinton Combined — by a lot.” The Washington Post. 20 June 2016.

Collins, Patricia Hill. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment. NY: Routledge, 2000 [1990].

Crenshaw, Kimberlé. “Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color.” Stanford Law Review 43.6 (Jul. 1991): 1241-1299.

Magnus, Josh. “Millennials Aren’t Satisfied with Capitalism — and Might Prefer a Socialist Country, Studies Find” Miami Herald. 4 Nov. 2017.

Rampel, Catherine. “Millennials Have a Higher Opinion of Socialism than of Capitalism.” The Washington Post. 5 February 2016.

West, Cornel. “Ta-Nehisi Coates is the Neoliberal Face of the Black Freedom Struggle.” The Guardian. 17 December 2017.

Williams, Douglas. “Why the Democratic Socialists of America are Experiencing a Boom.” The Guardian. 20 August 2017.